It’s hard to avoid talking about the news these days. Objectively terrible things are happening across the United States (and in quite a few other places too). These huge, terrible events are shattered across a hundred million headlines, plastered across every megabite of the Internet, and drip fed to us each waking hour, ceaselessly. In marginally saner times, the Internet monster occasionally belches up something frivolous, like arguments about the color of a dress or definition of a sandwich. Maybe that’s still happening, but current events mean it’s easier than ever to have an all-cataclysm media diet.

I’ve been dealing with this by trying to get rooted in my local community. I’m extremely lucky to have a strong radical/leftist/anarchist community where I live, and they have lots of great direct action1 projects to get involved with. I’ve put some time and energy into the local bail fund. I might not be able to do anything about mass deportation, but I can play a direct role in helping local people get out of cages. It feels good.

While attending bail fund meetings, I started to notice something interesting. Even during the craziest, scariest headlines about Trump’s abuse of power, my friends at the bail fund stayed relatively calm. All of my other conversations and virtually all of my text message threads would be about the latest assault on democracy. After a while, it just became the expected thing to mention, even if just briefly. I might be doing “fine, thanks” but I should probably save a moment to mention how scary the rest of the country is. But the most radical people I knew didn’t seem to be following this script2.

From one perspective, this sangfroid from the anarchist set is surprising. Their vision of utopia is already significantly removed from the status quo; under Trump, things are changing such that the anarchist vision is even more distant. Rank and file Democrats might be upset about asylum seekers being thrown in detention camps, but anarchists should be upset about asylum seekers AND all other prisoners.

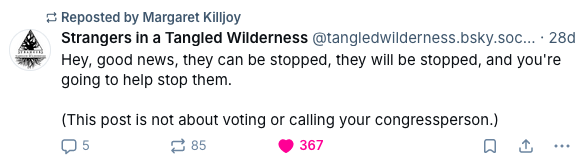

So why are some of the most radical among us also the best at taking current events in stride? I think there are probably two things that explain this phenomenon. First, I think lots of leftists already have a negative view of the status quo3. Indeed, the thing that often animates their politics is an acute awareness of widespread injustice. Like they said over at the wonderful Live Like the World is Dying podcast, “We’re moving from neoliberal hell to a fascist hell.” This isn’t an excuse to be smug, and the current situation is still bad in new and upsetting ways. Luckily, many of the things we need to do to respond to this fresh new hell are things that leftists are already doing.

This leads into the second point. Leftists (and perhaps anarchists in particular) are are experienced in building support structures that don’t rely on the government. Whether it’s feeding children, producing lifesaving medication, providing disaster relief, giving people Internet access, paving roads, or providing other services, people on the left have practiced myriad ways of supporting each other. Trump and co. decimating the federal government is very bad, for many reasons. But just because the FDA and FEMA aren’t doing their jobs doesn’t mean it’s impossible to get the services they provide.

Obviously anarchists do get ulcers. (The title of this post is just a riff on a Robert Sapolsky book.) This is a very stressful time for anyone who gives a shit about human suffering. There is some solace to be taken from the fact that lots and lots of people are already working on solutions. It’s not going to replace what’s being lost, not yet. But if you help, we can get a little closer.