Ziz: I was vaguely aware that the term “leviathan” referred to a creature with biblical-ish origins. And while I knew the word “behemoth,” I didn’t know it referred to a specific (fictional) creature, also from Jewish mythology. What I definitely didn’t know is that the leviathan and behemoth have an airborne cousin, the ziz. It is a bird said to be so huge that it can stand on the floor of the ocean with the water only reaching its ankles, and it lays eggs so massive that if they crack open they’ll flood sixty cities.

Three Hares: This is such a neat factoid I’m surprised I’ve never heard about it before. There’s a very specific art motif that features three rabbits arranged in a circle such that their ears are overlapping, and this symbol has popped up through through vast spans of time and space. The earliest examples we know of came from Chinese caves between the years 500 and 700. Later, the symbol appears in Islamic art in the late 1200s to early 1300s. Later still, it appears in western Europe, and even becomes particularly prevalent in the churches of southwestern England. There’s a theory that the symbol gradually diffused out of China along the “silk road” trading route. (For reasons I can’t really explain, this is my favorite hypothesis.) Others guess that the motif rose at least partially independently, and point out a long history of similar symbols in Celtic culture. One of the fun things about the Wikipedia article is reading all the different meanings the symbol had across times and places: everything from water to luck to the holy trinity to the Jewish diaspora.

Peter Lamborn Wilson: I came across Wilson as the person who coined the term “temporary autonomous zone” (TAZ). It’s a kinda useful, kinda fun idea about how we can make spaces that are mostly free of social control and use them to experiment with different ways of being. TAZs still get talked about a fair amount in anarchist circles, from what I can tell, though sometimes with some some caveats about Wilson’s personal life. In reading out his life on Wikipedia, two things jump out at me.

First the big one: apparently he also wrote for NAMBLA? I haven’t tracked down those writings and don’t care to, but they have been characterized by others (including Wilson’s former friends) as promoting sex between adults and children. So that fucking sucks. It’s weird how often this sort of thing crops up. Science fiction grand master Samuel Delany is a queer champion but also a supporter of NAMBLA1. (Both Wilson and Delany have had criticisms and mentions of pedophilia downplayed in their Wikipedia articles in the last year, which is disturbing). As this great thread on /r/AskHistorians points out, philosophers like Michel Foucault and Jean-Paul Sartre signed a petition against age of consent laws. I think you find predators in every walk of life, and they often manipulate whatever ideas they have at their disposal to persuade others2.

Second, Wilson was seemingly obsessed with other cultures, particularly Islam. That’s always a phenomenon that interests me. On one end of the respectability spectrum, you have have college professors and anthropologists who specialize in this or that. At the other end, you have folks like Iron Eyes Cody or Rachel Dolezal who engage in 24-7 cosplay as a member of a different group. Wilson didn’t quite go that far, but he did convert his religion and produce a lot of his writing under an ethnic pen name. I want to better understand why people get involved with that sort of cultural adoption. That means I’ll probably mentally bookmark Wilson as a case study but never look much further because focused research isn’t actually fun for me.

Anyway, TAZs are a cool concept. I think it’s important to recognize value in social experiments even if they don’t last for a long time.

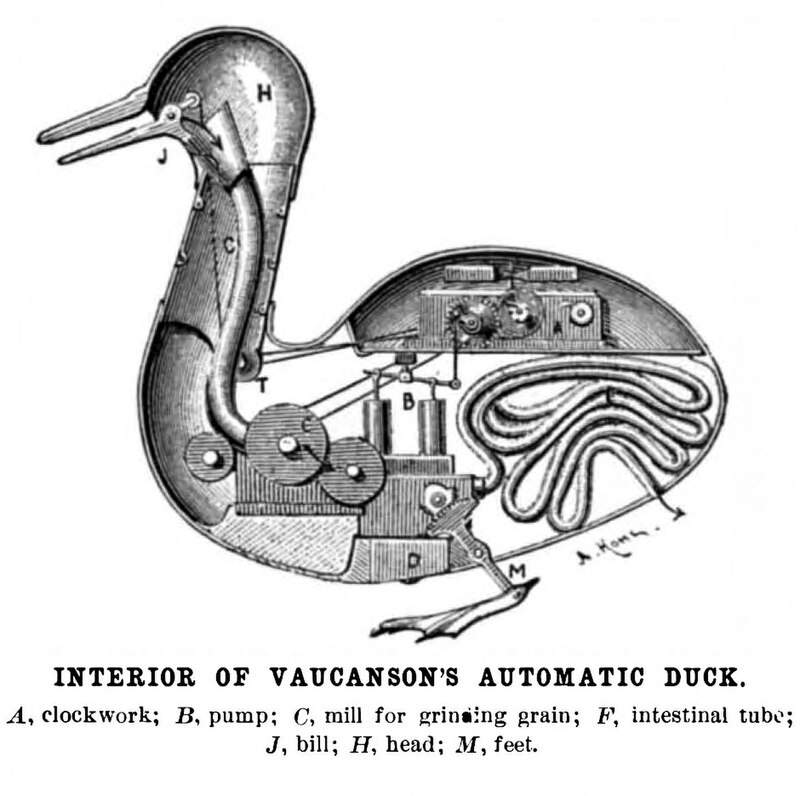

Digesting Duck: When I was in middle or high school, I read about an art instillation where some weirdo built a complex machine that mimicked human digestion. Food would be pushed in one end, get processed, and exit the other end as artificially-made shit3. The shits would then be vacuum sealed and sold to art collectors4. Anyway, the artist was (knowingly or not) working in conversation with Jacques de Vaucanson, a 1700s French inventor who created various machines and automata, including a mechanical duck that “ate” food out of the operator’s hand. Then, through some jiggery-pokery, the brass duck would appear to poop out the remains of the food. In reality, the food went into an internal pouch, while the “poop” (small, balled-up pieces of bread that were dyed green) were pre-loaded in a separate pouch. People at the time went gaga for the fake metal poop machine. The duck was lost in a fire, but has a robust afterlife making cameos in literature by everyone from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Frank Herbert.

- There’s a complex history between queer folks and organizations like NAMBLA that is beyond the scope of my knowledge but which surely provides important context. ↩︎

- According to the scant information on Wikipedia, there’s no evidence that Wilson abused children himself. Whether he was persuaded to his views by an abuser or came to them himself I don’t know. ↩︎

- Arguably an early example of machines taking over creative jobs. If you’re anti-AI, you shouldn’t settle for anything less than the real thing (SFW link, except for language). ↩︎

- The jokes write themselves. ↩︎